OMAR HASSAN H.O.2

The only thing that one really knows about human nature is that it changes.(Oscar Wilde)

In an artist's consciousness, different experiences are always piling up and blending together, impulses and antithetical needs oppose one another, conflicting memories and histories accumulate. Rarely is an expressive form born already completed, like an immobile construction, a clean, clear archetype that the artist lavishly translates into images or objects. More frequently, a style, a method or an attitude are the products of inner conflict, a forced synthesis, a difficult reconciliation. Bruno Munari said that "Art is a never-ending search, an assimilation of past experiences combined with new experiences, in the form, the content, the material, the technique, the means." In other words, something similar to an alchemical experience, which for the follower did not take the form of a journey through material and its chemical changes so much as a descent into the depths of the psyche. In Latin, the sentence E pluribus unum accurately defines the path accompanying the disciple from initial chaos to final synthesis. From the many to one. Something similar distinguishes the background of Omar Hassan, the young artist who made formal synthesis his distinctive mark.

The artist attended two schools: the Academy of Fine Arts and the street. And, in fact, the composition of dual impulses is the recurring theme in his artistic research.

Born to an Italian mother and Egyptian father in Milan in 1987, Omar Hassan grew up in a familiar atmosphere in which the Catholic and Muslim cultures were in peaceful dialogue. His upbringing was therefore the product of a hybridization, or rather of an integration of two radically different traditions, at least in terms of artistic representation: while Catholic art is highly figurative and tied to religious folk imagery, Islamic art is profoundly aniconic and centers on evolutions in calligraphy. Upon closer inspection, both influences come together in Omar Hassan's stylistic genome, in a sort of perfect syncretism between Eastern and Western heritage. But let us proceed in order.

As I have mentioned, with regards to Omar Hassan's paideia, his street experience played a fundamental role: frequenting the young Milanese street art scene where an artist must find his own original expressive form in an attempt to set himself apart in the jungle of styles and schools that characterize street art. For a street artist, originality is everything. The brand, the signature or tag and the method make the difference. Indeed, we could say that without his own originality, an artist cannot earn the respect of other writers. For a young artist like Omar Hassan, it would have been easier to fit in, choosing to dedicate himself to defining a tag, making his way through a hyperbolic variety of urban writing styles, or finding a way to dialogue with the pictorial styles of mural artists, who have returned to the canons of figurative representation. I have not ruled out the possibility that he may have attempted one of the two paths at the beginning, but at a certain point something in his blood came to the fore, like an unstoppable genetic impulse. Omar Hassan cleaned his slate of all conventional street art and went back to the starting point of street painting, recovering the gesture from which it draws its origin: a round, spray-painted dot, a burst of color spurting out from can of spray paint. This is the first syntagma of a writer's grammar, the first letter of the acrylic alphabet of a wall scribbler, nothing more than a round, dripping spot, vaguely similar to Niki De Saint Phalle's shooting paintings. For the nouveau realiste it was the effect of a rifle shot, but for Omar it is the result of paint sprayed from a can.

First one shot, then many shots. And thus, from one single letter a language was formed, articulated in purely chromatic extensions from a single form, like a binary code, simple and basic, but also terribly effective. Omar Hassan's sprayed paint is more than what appears to be at first glance, because in a single gesture it sums up the history of street art as an action, as a performance act, as action painting: physical, energetic, muscular, all within the elusive speed of the moment. Yet at the same time it gives new relevance to the meaning of so much of 20th-century avant-garde artistic research, which attempted a return to the pure, original forms of figurative art. I also sense in Omar Hassan's gesture a way of asserting the dignity of Islamic art, which draws its origins from the aniconic metality of nomadic desert tribes, the first to receive the message of the Prophet. In fact, it is not by chance that in previous works the artist pieced together a dialogue between abstract and calligraphic forms. Writing and letters are the ground on which both the Islamic arts and the tags of street art have evolved. With his sprayed signs, Omar Hassan symbolically bridges the gap between his biographical experience as a street artist and his father's cultural tradition. In thus doing, he also envisions a possible meeting ground between two different ways of conceiving of art: the Western and the Middle Eastern. But this is only the first form of synthesis. Another form involves healing the intimate disagreement that exists between the free forms of street art (and contemporary art in general) and those codified by classical art, which are (or ought to be) the foundation of an academic education.

As we have said, Hassan received his painting diploma at the Academy of Brera, where he was able to mature a certain knowledge of art history. This led him to consider that there might be another working domain beyond the city walls and gardens where he could test the ability of his gesture, that of fine arts, which demand a redefinition of work times, methods and intentions as compared to urban art. On the street, it is the projects' graphic impact, speed, quantity and location that count; but in painting on canvas, other factors play an important role: the gesture's effectiveness and necessity, its stylistic ability, a reflection on themes of formal order and, not lastly, the dialogue with art history and its evolution. Hence, Omar Hassan's problem becomes similar to that of other artists who, like him, have extended their field of action to the artistic system, as they call it. Examples in Italy might be Ericailcane, Ozmo, Bros, Pao, Dem, 108, Microbo and many others. This is not just a move to different supports, a trivial shift from wall to canvas, but a change in environment, an overturning of cultural and even behavioral reference norms.

Art is an insidious terrain beset with difficulties, bearing the weight of centuries of history. Yes, it is true that even street art has a history, but it is a recent one (the fact that some scholars date it to the latrinalia in Pompeii or even cave paintings is a real stretch of the imagination!).

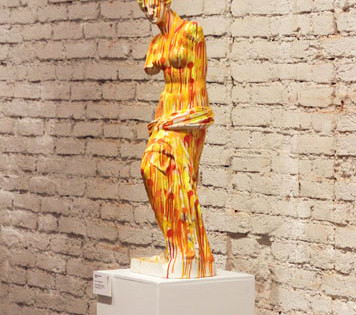

Omar Hassan converses with art history in the same way in which he faced the history of writing: he went back to its origins. And to him, the origin is classical art, academic art par excellence. It was not enough for him to spray his canvases with thousands of colors, including in his gestural frenzy the frames and even the surrounding walls. And it was not enough for him to give his own work instruments (cans of spray paint) the leading roles in works of a more than documentary value. Omar Hassan carried forward his original syntagma to anything he came across, even a flush toilet, a sort of allusion to Duchamp's famous urinal. But it was when he began to observe classical forms that his dialogue with art became more urgent. The casts of the Venus de Milo and the Nike of Samothrace immediately bring us back to the pretentious and somewhat dusty atmosphere of a cast gallery, to those exemplary models typical of academic instruction, so far from the painting methods of Omar Hassan. By facing those eternal forms, the artist has committed an act of humility and examination, almost as if he wished to test the validity of his mark on the temporal horizon of art history. Hassan's works on classical casts cannot be interpreted as extemporaneous, or even belated gestures of irreverence toward antique art. Rather, they are gestures of appropriation, and at the same time they give life to classical language. Without a doubt, sooner or later even urban art will rise to the importance of classical art. But in the meantime, at least for Hassan, this dialogue means a reordering of the creative impulses in a more adult dimension, which requires him to measure his language against the golden language of tradition. In the end, it is a comparison to which many artists subjected themselves, even in more recent history; one needs only think of Man Ray's Venus Restored, of Pistoletto's Venus of the Rags, of Return to Order in Picasso, to De Chirico, to Dalì and countless other 20th-century masters . This "correspondence of loving meanings" between the ancient and the modern worlds made up for a lack of comparison with nature itself and with an idea of beauty that seems quite out of date to us today. Johann Joachim Wincklemann wrote that "the difference between the Greeks and us" - and here he clearly alluded to the people of the 18th century - "is this: the Greeks succeeded in creating these images, even if they were not inspired by beautiful bodies, by means of the constant opportunity they had to observe the beauty in nature, which does not, however, show itself to us every day and rarely does it show itself as the artist would wish."

Imagine, now, how distant the concept of beauty in nature is from the mind of a street artist who has grown up in the middle of the jumbled metropolitan topography of a neighborhood like Lambrate, and how difficult it could be to assimilate an esthetic idea that finds no correspondence in his everyday life, and you will understand the extent of the risks that Omar Hassan agreed to take on. Accustomed to drawing symbols on walls, the artist has not only brought those same gestures to the canvas, those joyous marks made up of a multitude of colors: he has even transferred to them the most sacred icons of Western art, thus leading him to complete a further synthesis: that between the prosaic dimension of contemporary art and the auratic art of the golden age. And, in passing, we must remember that classical sculpture was polychrome and not monochrome, as it was left to us by Canova. Thus, Hassan is simply giving the dimension of color back to classical art.

Beside the winged Victories, the mutilated Venuses, given new life by a fragrant blossoming of synthetic color, Hassan provides us with a dissonant series of objects trouvés, of dump pickings, like the aforementioned toilet or a fridge filled with used cans of spray paint. This is one of the more jarring combinations, but it reveals the artist's intrinsic esthetic dichotomy. In Omar Hassan, the Dadaist practice of salvaging objects, by now a classic in contemporary culture, is pushed to the extreme. And thus, his very work instruments become a work of art.

Lined up and sealed in clear plastic cases, the empty cans of spray paint therefore become concrete and objective proof of a practice, while at the same time taking on an artistic value, a bit like the photographs that document performance art. An example of this are the works from the series Borgio Verezzi in Wonderland, which gathered together cans of spray paint used during the execution of a mural created by the Ligurian town of the same name. In this case, a single action gives rise to two different artistic expressions: the first, painting and performance, the second involving the ready made procedure. And here we have another synthesis, which this time brings together the age-old dichotomy between pictorial and conceptual practices. And further proof of this attitude is the fact that not only does the can of spray paint take on the value of a work of art, as in the above mentioned series: it even becomes the subject of a bronze sculpture, thus bringing to completion that process of absorbing classical art begun with spray-painting the plaster casts. This is a work that encapsulates the substance of this exchange between classical and modern art, because in it, the can of spray paint (equipped with five caps in the primary colors, black and white, almost as if to indicate the entire range of color) and the very act of spraying paint ascend to the monumental and hyperuranian importance of ancient art. It is, in essence, a sort of altar to writers, an idol offered up to the future memory of posterity.

In the art of Omar Hassan, everything seems to respond to this need for bridging the gap, this desire to join together influences, origins and the discordant elements of his life story. In analyzing a work, we never insist enough on biological elements, perhaps due to a kind of respectful reserve, but in the case of Hassan it is only right to say that the means and the method, beyond the spray can and spray-paint metaphor, have a precise meaning. They are instruments that serve to calculate the frequency of a daily gesture, like taking medicine, on his studio wall. Thus Omar Hassan's single sprayed mark is born, like an enumeration of vital importance, while waiting for the act to transform itself into automatism. Within that sprayed mark there is the very meaning of life, the sound of breath and the color of our days. And lastly, there is the desire to permeate every gesture and every object with this breath of energy. The same energy that the philosopher Henri Bergon called élan vital.

________________________________________________________________________

OMAR HASSAN. Due di uno.

di Ivan Quaroni

La sola cosa di cui si è certi a proposito

della natura umana, è che essa cambia.

(Oscar Wilde)

Sempre, nella coscienza di un artista, si affastellano e si confondono esperienze diverse, configgono impulsi e istanze antitetiche, si accumulano memorie e tracce di segno opposto. Raramente, una forma espressiva nasce già conclusa, come un costrutto immobile, un archetipo limpido, nitido, che l’artista doviziosamente traduce in immagini, in manufatti, in cose. Più spesso, uno stile, un modo, un’attitudine, sono i prodotti di un conflitto interiore, di una sintesi forzata, di una difficile pacificazione. Bruno Munari affermava che “L'arte è ricerca continua, assimilazione delle esperienze passate, aggiunta di esperienze nuove, nelle forma, nel contenuto, nella materia, nella tecnica, nei mezzi”. Insomma, qualcosa di simile all’esperienza alchemica, che si configurava, per il discepolo, non tanto come un viaggio nella materia e nelle sue alterazioni chimiche, quanto come una discesa negli inferi della psiche. In latino, la sentenza E pluribus unum, designa con precisione la traiettoria che accompagna l’allievo dal caos iniziale alla sintesi finale. Dal molteplice all’uno. Qualcosa di simile contraddistingue il background di Omar Hassan, giovane artista che della sintesi formale ha fatto il suo marchio distintivo.

L’artista ha, infatti, frequentato due scuole, una è l’Accademia di Belle Arti, l’altra è la strada. E proprio la composizione d’istanze duplici è il tema ricorrente della sua ricerca artistica.

Nato nel 1987 a Milano, da madre italiana e padre egiziano, Omar Hassan cresce in un clima familiare in cui si confrontano pacificamente la cultura cattolica e musulmana. La sua educazione è, quindi, già il frutto di un’ibridazione, o meglio di un’integrazione tra due tradizioni radicalmente diverse, almeno sul piano della rappresentazione artistica: ultrafigurativa e legata all’immaginario devozionale popolare, quella cattolica; profondamente aniconica e versata nelle evoluzioni della calligrafia, quella islamica. A ben vedere, entrambe confluiranno nel genoma stilistico di Omar Hassan, in una sorta di perfetto sincretismo tra i patrimoni orientale e occidentale. Ma procediamo con ordine.

Si diceva, a proposito della paideia di Omar Hassan, che un ruolo fondamentale l’ha giocato l’esperienza di strada, ossia la frequentazione dell’ambiente della giovane street art milanese, dove è necessario trovare una propria originale forma espressiva nel tentativo di distinguersi nella giungla di stili e scuole che la contraddistinguono. Per uno street artista l’originalità è tutto. Il marchio, la firma (tag), il modo fanno la differenza. Anzi, si può dire che senza una propria originalità l’artista non può guadagnarsi il rispetto degli altri writers. Per uno giovane come Omar Hassan sarebbe stato più semplice adeguarsi, scegliere di dedicarsi alla definizione di una tag, facendosi largo tra un’iperbolica varietà di calligrafie urbane, oppure trovare un modo di confrontarsi con gli stilemi pittorici dei muralisti, ritornati ai codici della rappresentazione figurativa. Non escludo che all’inizio abbia tentato una delle due strade, ma ad un certo punto qualcosa del suo DNA è tornato a galla, come un impulso genetico insopprimibile. Omar Hassan ha fatto piazza pulita di tutto ciò che era convenzionalmente street art ed è tornato al grado zero della pittura di strada, recuperando il gesto da cui tutto trae origine: uno spruzzo di forma circolare, un vagito di colore, schizzato dal foro d’uscita di una bomboletta spray. È il primo sintagma della grammatica di un writer, la prima lettera dell’alfabeto acrilico di un imbrattamuri, niente più che una macchia rotonda e sgocciolante, vagamente simile agli shooting paintings di Niki De Saint Phalle. Qualcosa che per la nouveau realiste era l’effetto di uno sparo di carabina, e per Omar è, invece, il risultato di uno spruzzo di bomboletta.

Prima un colpo, poi molti colpi. E così da una sola lettera si è formato un linguaggio, articolato in estensioni puramente cromatiche di una singola forma, come un codice binario, semplice ed elementare, ma anche maledettamente efficace. Lo spruzzo di Omar Hassan è più di quanto appaia a una prima occhiata, perché sintetizza in un solo gesto la storia della street art intesa come azione, come atto performativo, come action painting fisica, energetica, muscolare, tutta compresa nella velocità inafferrabile dell’attimo, ma allo stesso tempo riattualizza il senso di tante ricerche avanguardistiche del Novecento, che tentavano un ritorno alle forme pure e originarie della rappresentazione. Di più, colgo nel gesto di Omar Hassan anche un modo di rivendicare la dignità dell’arte islamica, che trae origine dalla mentalità aniconica delle tribù nomadi del deserto, che per prime accolsero il messaggio del Profeta. Non è casuale, infatti, che già in opere precedenti l’artista imbastisse un dialogo tra forme astratte e calligrafiche. La grafia e il carattere sono il terreno su cui si sono evolute sia le arti islamiche sia le tag della street art. Con i suoi segni spruzzati, Omar Hassan ricompone idealmente la frattura tra la sua esperienza biografica, di artista di strada e la tradizione culturale paterna. Così facendo, ipotizza anche un possibile terreno d’incontro tra due diversi modi di concepire l’arte, quello occidentale e quello mediorientale. Ma questa non è che la prima forma di sintesi. Un’altra riguarda la ricomposizione dell’intimo dissidio esistente tra le forme libere dell’arte di strada (e dell’arte contemporanea in genere) e quelle codificate dall’arte classica, che sono (o dovrebbero essere) il fondamento dell’educazione accademica.

Hassan, dicevamo, si è diplomato in pittura all’Accademia di Brera, dove ha potuto maturare una certa cognizione di storia dell’arte. Fatto che l’ha portato a considerare che, oltre ai muri e ai giardini cittadini esistesse un altro dominio operativo in cui verificare la tenuta del suo gesto, quello proprio delle fine arts, che impongono una ridefinizione di tempi, modi, intenzioni rispetto all’ambito urbano. Mentre in strada conta l’impatto grafico, la velocità, la quantità e la locazione degli interventi, nella pittura su tela giocano un ruolo importante altri fattori: la funzionalità e la necessità del gesto, la sua tenuta stilistica, la riflessione intorno ai motivi di ordine formale e, non ultimo, il confronto con la storia dell’arte e le sue evoluzioni. Allora, il problema di Omar Hassan diventa simile a quello di altri artisti che, come lui, hanno esteso il proprio terreno d’azione all’ambito del sistema artistico propriamente detto. Penso, in Italia, a Ericailcane, Ozmo, Bros, Pao, Dem, 108, Microbo e molti altri. Non si tratta solo di un passaggio che riguarda i supporti, di un banale slittamento dal muro alla tela, ma di un cambiamento di ambiente, di un capovolgimento dei codici di riferimento culturali e anche comportamentali.

L’arte è un terreno insidioso, irto di difficoltà, su cui incombe il peso di secoli di storia. Sì, è vero che anche la street art ha una storia, ma è una storia recente (il fatto che alcuni studiosi la facciano risalire ai latrinalia pompeiani o perfino alle pitture rupestri è una forzatura bella e buona!).

Omar Hassan si confronta con la storia dell’arte nello stesso modo con cui si è confrontato con la storia del writing: è tornato all’origine. E l’origine, per lui, è l’arte classica, quella accademica per eccellenza. Non gli è bastato imbrattare le tele di migliaia di spruzzi colorati, includendo nella sua furia gestuale le cornici e perfino i muri circostanti. Non gli è bastato, nemmeno, fare dei propri strumenti di lavoro (le bombolette spray) i protagonisti di opere dal valore più che documentario. Omar Hassan ha portato il suo sintagma originario su qualsiasi cosa gli è capitata sottomano, perfino un water closet, sorta di allusione al famoso orinatoio duchampiano, ma è quando ha iniziato a guardare alle forme classiche che il confronto con l’arte si è fatto più stringente. I gessi della Venere di Milo e della Nike di Samotracia rimandano immediatamente all’atmosfera paludata e un po’ passita di una gipsoteca, a quell’esemplarità di modelli tipica dell’insegnamento accademico, così lontana dai modi della pittura di Omar Hassan. Confrontandosi con quelle forme imperiture, l’artista compie un atto di umiltà e di verifica, quasi volesse testare la validità del suo segno nell’orizzonte temporale della storia dell’arte. Non si possono interpretare gli interventi di Hassan sui calchi classici come estemporanei, quanto tardivi, gesti d’irriverenza verso l’antico. Si tratta piuttosto di gesti di appropriazione e, insieme, di vivificazione del linguaggio classico. Non c’è dubbio che, presto o tardi, anche l’arte urbana assurgerà alla dimensione del classico. Ma, intanto, almeno per Hassan, questo dialogo ha il senso di un riordinamento delle pulsioni creative in una dimensione più adulta, che lo obbliga a misurare il proprio linguaggio con quello aureo della tradizione. In fondo, è un confronto cui molti artisti si sono sottoposti anche nella storia più recente, basti pensare alla Venere restaurata di Man Ray, alla Venere degli stracci di Pistoletto, al Picasso del Ritorno all’Ordine, a De Chirico, a Dalì e a numerosissimi altri maestri del Novecento. Questa “corrispondenza d’amorosi sensi” tra l’antico e il moderno suppliva a una mancanza di confronto con la natura stessa e con un’idea di bellezza che a noi contemporanei sembra quanto mai inattuale. Johann Johachim Wincklemann scriveva che “la differenza fra i greci e noi” - e alludeva ovviamente agli uomini del Settecento – “sta in questo: che i greci riuscirono a creare queste immagini, anche se non ispirate da corpi belli, per mezzo della continua occasione che avevano di osservare il bello della natura: la quale, invece, a noi non si mostra tutti i giorni e raramente si mostra come l’artista la vorrebbe”.

Immaginate, ora, quanto il concetto del bello in natura sia distante dalla mente di uno street artista, cresciuto in mezzo alla disarticolata topografia metropolitana di un quartiere come Lambrate, e quanto difficile possa essere l’assimilazione di un ideale estetico che non trova alcun riscontro nella sua quotidianità, e avrete la misura dei rischi che Omar Hassan ha accettato di correre. Abituato a tracciare segni sul muro, l’artista non solo ha riportato su tela quegli stessi gesti, quelle impronte gioiose formate da una moltitudine di colori, ma le ha trasferite perfino sulle icone più sacre dell’arte occidentale, portando, così, a compimento un’ulteriore sintesi: quella tra la dimensione prosaica dell’arte contemporanea e quella auratica dell’età dell’oro. E, en passant, è bene ricordare che la scultura classica era policroma e non monocroma, come tramandatoci dal Canova. Dunque, Hassan non fa che restituire alla classicità la dimensione del colore.

Accanto alle Vittorie alate, alle Veneri mutile, rianimate da una fragrante fioritura di colori sintetici, Hassan dispone, infatti, una serie dissonante di objects trouvés, di scarti da discarica, come il succitato WC o un frigorifero riempito di bombolette usate. L’accostamento è dei più stridenti, ma rivela l’intrinseca dicotomia estetica dell’artista. La pratica dadaista del recupero, già divenuta un classico nella contemporaneità, si spinge in Omar Hassan fino a esiti estremi. E così, i suoi stessi strumenti di lavoro, diventano un’opera d’arte.

Allineate e sigillate in teche di perpex, le bombolette esauste diventano, quindi, traccia concreta e testimonianza oggettiva di una pratica, assumendo al contempo una valenza artistica, un po’ come accade per le foto che documentano le azioni performative. Ne sono un esempio, le opere della serie Borgio Verezzi in wonderland, che assemblano le bombolette consumate durante l’esecuzione di un dipinto murale eseguito nell’omonima cittadina ligure. Da una sola azione, in questo caso, nascono due diverse espressioni artistiche, la prima pittorica e performativa, la seconda inerente la prassi del ready made. Ed ecco un’altra sintesi, che questa volta ricompone l’annosa dicotomia tra pratiche pittoriche e concettuali. E la riprova di questa attitudine è il fatto che non solo la bomboletta spray assume il valore di opera d’arte, come nella succitata serie, ma diventa perfino il soggetto di una scultura bronzea, portando così a compimento quel processo di fagocitazione del classico, iniziato con gli spruzzi sui calchi in gesso. Si tratta di un’opera che racchiude la sostanza di questo scambio tra classicità e modernità, poiché in essa, la bomboletta (dotata di cinque tappi con i colori primari, il bianco e il nero, quasi a indicare tutta l’estensione della gamma cromatica) e l’atto stesso di spruzzare vernice, ascendono alla dimensione monumentale e iperurania dell’antico. Si tratta, in definitiva, di una sorta di altare dei writer, un idolo consegnato alla futura memoria dei posteri.

Nell’arte di Omar Hassan tutto sembra rispondere a questa necessità di ricomposizione, a questa volontà di unificare influenze, matrici ed elementi discordanti della sua biografia. Non si insiste mai abbastanza, nell’analisi di una ricerca, sugli elementi biografici, forse per una sorta di riguardoso pudore, ma nel caso di Hassan è lecito almeno dire che il mezzo e il modo, fuor di metafora la bomboletta e lo spruzzo, hanno un significato preciso. Sono strumenti che servivano a computare sul muro del suo studio la frequenza di un gesto quotidiano, l’assunzione di un farmaco. Nasce così lo spruzzo singolo di Omar Hassan, come una enumerazione di vitale importanza, in attesa che presto l’atto si trasformi in automatismo. Così, dentro quello spruzzo di spray c’è il senso stesso della vita, c’è il suono del respiro e il colore dei giorni. E, infine, c’è la volontà di permeare ogni gesto e ogni cosa con questo soffio di energia. La stessa che il filosofo Henri Bergson definiva élan vital.

In an artist's consciousness, different experiences are always piling up and blending together, impulses and antithetical needs oppose one another, conflicting memories and histories accumulate. Rarely is an expressive form born already completed, like an immobile construction, a clean, clear archetype that the artist lavishly translates into images or objects. More frequently, a style, a method or an attitude are the products of inner conflict, a forced synthesis, a difficult reconciliation. Bruno Munari said that "Art is a never-ending search, an assimilation of past experiences combined with new experiences, in the form, the content, the material, the technique, the means." In other words, something similar to an alchemical experience, which for the follower did not take the form of a journey through material and its chemical changes so much as a descent into the depths of the psyche. In Latin, the sentence E pluribus unum accurately defines the path accompanying the disciple from initial chaos to final synthesis. From the many to one. Something similar distinguishes the background of Omar Hassan, the young artist who made formal synthesis his distinctive mark.

The artist attended two schools: the Academy of Fine Arts and the street. And, in fact, the composition of dual impulses is the recurring theme in his artistic research.

Born to an Italian mother and Egyptian father in Milan in 1987, Omar Hassan grew up in a familiar atmosphere in which the Catholic and Muslim cultures were in peaceful dialogue. His upbringing was therefore the product of a hybridization, or rather of an integration of two radically different traditions, at least in terms of artistic representation: while Catholic art is highly figurative and tied to religious folk imagery, Islamic art is profoundly aniconic and centers on evolutions in calligraphy. Upon closer inspection, both influences come together in Omar Hassan's stylistic genome, in a sort of perfect syncretism between Eastern and Western heritage. But let us proceed in order.

As I have mentioned, with regards to Omar Hassan's paideia, his street experience played a fundamental role: frequenting the young Milanese street art scene where an artist must find his own original expressive form in an attempt to set himself apart in the jungle of styles and schools that characterize street art. For a street artist, originality is everything. The brand, the signature or tag and the method make the difference. Indeed, we could say that without his own originality, an artist cannot earn the respect of other writers. For a young artist like Omar Hassan, it would have been easier to fit in, choosing to dedicate himself to defining a tag, making his way through a hyperbolic variety of urban writing styles, or finding a way to dialogue with the pictorial styles of mural artists, who have returned to the canons of figurative representation. I have not ruled out the possibility that he may have attempted one of the two paths at the beginning, but at a certain point something in his blood came to the fore, like an unstoppable genetic impulse. Omar Hassan cleaned his slate of all conventional street art and went back to the starting point of street painting, recovering the gesture from which it draws its origin: a round, spray-painted dot, a burst of color spurting out from can of spray paint. This is the first syntagma of a writer's grammar, the first letter of the acrylic alphabet of a wall scribbler, nothing more than a round, dripping spot, vaguely similar to Niki De Saint Phalle's shooting paintings. For the nouveau realiste it was the effect of a rifle shot, but for Omar it is the result of paint sprayed from a can.

First one shot, then many shots. And thus, from one single letter a language was formed, articulated in purely chromatic extensions from a single form, like a binary code, simple and basic, but also terribly effective. Omar Hassan's sprayed paint is more than what appears to be at first glance, because in a single gesture it sums up the history of street art as an action, as a performance act, as action painting: physical, energetic, muscular, all within the elusive speed of the moment. Yet at the same time it gives new relevance to the meaning of so much of 20th-century avant-garde artistic research, which attempted a return to the pure, original forms of figurative art. I also sense in Omar Hassan's gesture a way of asserting the dignity of Islamic art, which draws its origins from the aniconic metality of nomadic desert tribes, the first to receive the message of the Prophet. In fact, it is not by chance that in previous works the artist pieced together a dialogue between abstract and calligraphic forms. Writing and letters are the ground on which both the Islamic arts and the tags of street art have evolved. With his sprayed signs, Omar Hassan symbolically bridges the gap between his biographical experience as a street artist and his father's cultural tradition. In thus doing, he also envisions a possible meeting ground between two different ways of conceiving of art: the Western and the Middle Eastern. But this is only the first form of synthesis. Another form involves healing the intimate disagreement that exists between the free forms of street art (and contemporary art in general) and those codified by classical art, which are (or ought to be) the foundation of an academic education.

As we have said, Hassan received his painting diploma at the Academy of Brera, where he was able to mature a certain knowledge of art history. This led him to consider that there might be another working domain beyond the city walls and gardens where he could test the ability of his gesture, that of fine arts, which demand a redefinition of work times, methods and intentions as compared to urban art. On the street, it is the projects' graphic impact, speed, quantity and location that count; but in painting on canvas, other factors play an important role: the gesture's effectiveness and necessity, its stylistic ability, a reflection on themes of formal order and, not lastly, the dialogue with art history and its evolution. Hence, Omar Hassan's problem becomes similar to that of other artists who, like him, have extended their field of action to the artistic system, as they call it. Examples in Italy might be Ericailcane, Ozmo, Bros, Pao, Dem, 108, Microbo and many others. This is not just a move to different supports, a trivial shift from wall to canvas, but a change in environment, an overturning of cultural and even behavioral reference norms.

Art is an insidious terrain beset with difficulties, bearing the weight of centuries of history. Yes, it is true that even street art has a history, but it is a recent one (the fact that some scholars date it to the latrinalia in Pompeii or even cave paintings is a real stretch of the imagination!).

Omar Hassan converses with art history in the same way in which he faced the history of writing: he went back to its origins. And to him, the origin is classical art, academic art par excellence. It was not enough for him to spray his canvases with thousands of colors, including in his gestural frenzy the frames and even the surrounding walls. And it was not enough for him to give his own work instruments (cans of spray paint) the leading roles in works of a more than documentary value. Omar Hassan carried forward his original syntagma to anything he came across, even a flush toilet, a sort of allusion to Duchamp's famous urinal. But it was when he began to observe classical forms that his dialogue with art became more urgent. The casts of the Venus de Milo and the Nike of Samothrace immediately bring us back to the pretentious and somewhat dusty atmosphere of a cast gallery, to those exemplary models typical of academic instruction, so far from the painting methods of Omar Hassan. By facing those eternal forms, the artist has committed an act of humility and examination, almost as if he wished to test the validity of his mark on the temporal horizon of art history. Hassan's works on classical casts cannot be interpreted as extemporaneous, or even belated gestures of irreverence toward antique art. Rather, they are gestures of appropriation, and at the same time they give life to classical language. Without a doubt, sooner or later even urban art will rise to the importance of classical art. But in the meantime, at least for Hassan, this dialogue means a reordering of the creative impulses in a more adult dimension, which requires him to measure his language against the golden language of tradition. In the end, it is a comparison to which many artists subjected themselves, even in more recent history; one needs only think of Man Ray's Venus Restored, of Pistoletto's Venus of the Rags, of Return to Order in Picasso, to De Chirico, to Dalì and countless other 20th-century masters . This "correspondence of loving meanings" between the ancient and the modern worlds made up for a lack of comparison with nature itself and with an idea of beauty that seems quite out of date to us today. Johann Joachim Wincklemann wrote that "the difference between the Greeks and us" - and here he clearly alluded to the people of the 18th century - "is this: the Greeks succeeded in creating these images, even if they were not inspired by beautiful bodies, by means of the constant opportunity they had to observe the beauty in nature, which does not, however, show itself to us every day and rarely does it show itself as the artist would wish."

Imagine, now, how distant the concept of beauty in nature is from the mind of a street artist who has grown up in the middle of the jumbled metropolitan topography of a neighborhood like Lambrate, and how difficult it could be to assimilate an esthetic idea that finds no correspondence in his everyday life, and you will understand the extent of the risks that Omar Hassan agreed to take on. Accustomed to drawing symbols on walls, the artist has not only brought those same gestures to the canvas, those joyous marks made up of a multitude of colors: he has even transferred to them the most sacred icons of Western art, thus leading him to complete a further synthesis: that between the prosaic dimension of contemporary art and the auratic art of the golden age. And, in passing, we must remember that classical sculpture was polychrome and not monochrome, as it was left to us by Canova. Thus, Hassan is simply giving the dimension of color back to classical art.

Beside the winged Victories, the mutilated Venuses, given new life by a fragrant blossoming of synthetic color, Hassan provides us with a dissonant series of objects trouvés, of dump pickings, like the aforementioned toilet or a fridge filled with used cans of spray paint. This is one of the more jarring combinations, but it reveals the artist's intrinsic esthetic dichotomy. In Omar Hassan, the Dadaist practice of salvaging objects, by now a classic in contemporary culture, is pushed to the extreme. And thus, his very work instruments become a work of art.

Lined up and sealed in clear plastic cases, the empty cans of spray paint therefore become concrete and objective proof of a practice, while at the same time taking on an artistic value, a bit like the photographs that document performance art. An example of this are the works from the series Borgio Verezzi in Wonderland, which gathered together cans of spray paint used during the execution of a mural created by the Ligurian town of the same name. In this case, a single action gives rise to two different artistic expressions: the first, painting and performance, the second involving the ready made procedure. And here we have another synthesis, which this time brings together the age-old dichotomy between pictorial and conceptual practices. And further proof of this attitude is the fact that not only does the can of spray paint take on the value of a work of art, as in the above mentioned series: it even becomes the subject of a bronze sculpture, thus bringing to completion that process of absorbing classical art begun with spray-painting the plaster casts. This is a work that encapsulates the substance of this exchange between classical and modern art, because in it, the can of spray paint (equipped with five caps in the primary colors, black and white, almost as if to indicate the entire range of color) and the very act of spraying paint ascend to the monumental and hyperuranian importance of ancient art. It is, in essence, a sort of altar to writers, an idol offered up to the future memory of posterity.

In the art of Omar Hassan, everything seems to respond to this need for bridging the gap, this desire to join together influences, origins and the discordant elements of his life story. In analyzing a work, we never insist enough on biological elements, perhaps due to a kind of respectful reserve, but in the case of Hassan it is only right to say that the means and the method, beyond the spray can and spray-paint metaphor, have a precise meaning. They are instruments that serve to calculate the frequency of a daily gesture, like taking medicine, on his studio wall. Thus Omar Hassan's single sprayed mark is born, like an enumeration of vital importance, while waiting for the act to transform itself into automatism. Within that sprayed mark there is the very meaning of life, the sound of breath and the color of our days. And lastly, there is the desire to permeate every gesture and every object with this breath of energy. The same energy that the philosopher Henri Bergon called élan vital.

________________________________________________________________________

OMAR HASSAN. Due di uno.

di Ivan Quaroni

La sola cosa di cui si è certi a proposito

della natura umana, è che essa cambia.

(Oscar Wilde)

Sempre, nella coscienza di un artista, si affastellano e si confondono esperienze diverse, configgono impulsi e istanze antitetiche, si accumulano memorie e tracce di segno opposto. Raramente, una forma espressiva nasce già conclusa, come un costrutto immobile, un archetipo limpido, nitido, che l’artista doviziosamente traduce in immagini, in manufatti, in cose. Più spesso, uno stile, un modo, un’attitudine, sono i prodotti di un conflitto interiore, di una sintesi forzata, di una difficile pacificazione. Bruno Munari affermava che “L'arte è ricerca continua, assimilazione delle esperienze passate, aggiunta di esperienze nuove, nelle forma, nel contenuto, nella materia, nella tecnica, nei mezzi”. Insomma, qualcosa di simile all’esperienza alchemica, che si configurava, per il discepolo, non tanto come un viaggio nella materia e nelle sue alterazioni chimiche, quanto come una discesa negli inferi della psiche. In latino, la sentenza E pluribus unum, designa con precisione la traiettoria che accompagna l’allievo dal caos iniziale alla sintesi finale. Dal molteplice all’uno. Qualcosa di simile contraddistingue il background di Omar Hassan, giovane artista che della sintesi formale ha fatto il suo marchio distintivo.

L’artista ha, infatti, frequentato due scuole, una è l’Accademia di Belle Arti, l’altra è la strada. E proprio la composizione d’istanze duplici è il tema ricorrente della sua ricerca artistica.

Nato nel 1987 a Milano, da madre italiana e padre egiziano, Omar Hassan cresce in un clima familiare in cui si confrontano pacificamente la cultura cattolica e musulmana. La sua educazione è, quindi, già il frutto di un’ibridazione, o meglio di un’integrazione tra due tradizioni radicalmente diverse, almeno sul piano della rappresentazione artistica: ultrafigurativa e legata all’immaginario devozionale popolare, quella cattolica; profondamente aniconica e versata nelle evoluzioni della calligrafia, quella islamica. A ben vedere, entrambe confluiranno nel genoma stilistico di Omar Hassan, in una sorta di perfetto sincretismo tra i patrimoni orientale e occidentale. Ma procediamo con ordine.

Si diceva, a proposito della paideia di Omar Hassan, che un ruolo fondamentale l’ha giocato l’esperienza di strada, ossia la frequentazione dell’ambiente della giovane street art milanese, dove è necessario trovare una propria originale forma espressiva nel tentativo di distinguersi nella giungla di stili e scuole che la contraddistinguono. Per uno street artista l’originalità è tutto. Il marchio, la firma (tag), il modo fanno la differenza. Anzi, si può dire che senza una propria originalità l’artista non può guadagnarsi il rispetto degli altri writers. Per uno giovane come Omar Hassan sarebbe stato più semplice adeguarsi, scegliere di dedicarsi alla definizione di una tag, facendosi largo tra un’iperbolica varietà di calligrafie urbane, oppure trovare un modo di confrontarsi con gli stilemi pittorici dei muralisti, ritornati ai codici della rappresentazione figurativa. Non escludo che all’inizio abbia tentato una delle due strade, ma ad un certo punto qualcosa del suo DNA è tornato a galla, come un impulso genetico insopprimibile. Omar Hassan ha fatto piazza pulita di tutto ciò che era convenzionalmente street art ed è tornato al grado zero della pittura di strada, recuperando il gesto da cui tutto trae origine: uno spruzzo di forma circolare, un vagito di colore, schizzato dal foro d’uscita di una bomboletta spray. È il primo sintagma della grammatica di un writer, la prima lettera dell’alfabeto acrilico di un imbrattamuri, niente più che una macchia rotonda e sgocciolante, vagamente simile agli shooting paintings di Niki De Saint Phalle. Qualcosa che per la nouveau realiste era l’effetto di uno sparo di carabina, e per Omar è, invece, il risultato di uno spruzzo di bomboletta.

Prima un colpo, poi molti colpi. E così da una sola lettera si è formato un linguaggio, articolato in estensioni puramente cromatiche di una singola forma, come un codice binario, semplice ed elementare, ma anche maledettamente efficace. Lo spruzzo di Omar Hassan è più di quanto appaia a una prima occhiata, perché sintetizza in un solo gesto la storia della street art intesa come azione, come atto performativo, come action painting fisica, energetica, muscolare, tutta compresa nella velocità inafferrabile dell’attimo, ma allo stesso tempo riattualizza il senso di tante ricerche avanguardistiche del Novecento, che tentavano un ritorno alle forme pure e originarie della rappresentazione. Di più, colgo nel gesto di Omar Hassan anche un modo di rivendicare la dignità dell’arte islamica, che trae origine dalla mentalità aniconica delle tribù nomadi del deserto, che per prime accolsero il messaggio del Profeta. Non è casuale, infatti, che già in opere precedenti l’artista imbastisse un dialogo tra forme astratte e calligrafiche. La grafia e il carattere sono il terreno su cui si sono evolute sia le arti islamiche sia le tag della street art. Con i suoi segni spruzzati, Omar Hassan ricompone idealmente la frattura tra la sua esperienza biografica, di artista di strada e la tradizione culturale paterna. Così facendo, ipotizza anche un possibile terreno d’incontro tra due diversi modi di concepire l’arte, quello occidentale e quello mediorientale. Ma questa non è che la prima forma di sintesi. Un’altra riguarda la ricomposizione dell’intimo dissidio esistente tra le forme libere dell’arte di strada (e dell’arte contemporanea in genere) e quelle codificate dall’arte classica, che sono (o dovrebbero essere) il fondamento dell’educazione accademica.

Hassan, dicevamo, si è diplomato in pittura all’Accademia di Brera, dove ha potuto maturare una certa cognizione di storia dell’arte. Fatto che l’ha portato a considerare che, oltre ai muri e ai giardini cittadini esistesse un altro dominio operativo in cui verificare la tenuta del suo gesto, quello proprio delle fine arts, che impongono una ridefinizione di tempi, modi, intenzioni rispetto all’ambito urbano. Mentre in strada conta l’impatto grafico, la velocità, la quantità e la locazione degli interventi, nella pittura su tela giocano un ruolo importante altri fattori: la funzionalità e la necessità del gesto, la sua tenuta stilistica, la riflessione intorno ai motivi di ordine formale e, non ultimo, il confronto con la storia dell’arte e le sue evoluzioni. Allora, il problema di Omar Hassan diventa simile a quello di altri artisti che, come lui, hanno esteso il proprio terreno d’azione all’ambito del sistema artistico propriamente detto. Penso, in Italia, a Ericailcane, Ozmo, Bros, Pao, Dem, 108, Microbo e molti altri. Non si tratta solo di un passaggio che riguarda i supporti, di un banale slittamento dal muro alla tela, ma di un cambiamento di ambiente, di un capovolgimento dei codici di riferimento culturali e anche comportamentali.

L’arte è un terreno insidioso, irto di difficoltà, su cui incombe il peso di secoli di storia. Sì, è vero che anche la street art ha una storia, ma è una storia recente (il fatto che alcuni studiosi la facciano risalire ai latrinalia pompeiani o perfino alle pitture rupestri è una forzatura bella e buona!).

Omar Hassan si confronta con la storia dell’arte nello stesso modo con cui si è confrontato con la storia del writing: è tornato all’origine. E l’origine, per lui, è l’arte classica, quella accademica per eccellenza. Non gli è bastato imbrattare le tele di migliaia di spruzzi colorati, includendo nella sua furia gestuale le cornici e perfino i muri circostanti. Non gli è bastato, nemmeno, fare dei propri strumenti di lavoro (le bombolette spray) i protagonisti di opere dal valore più che documentario. Omar Hassan ha portato il suo sintagma originario su qualsiasi cosa gli è capitata sottomano, perfino un water closet, sorta di allusione al famoso orinatoio duchampiano, ma è quando ha iniziato a guardare alle forme classiche che il confronto con l’arte si è fatto più stringente. I gessi della Venere di Milo e della Nike di Samotracia rimandano immediatamente all’atmosfera paludata e un po’ passita di una gipsoteca, a quell’esemplarità di modelli tipica dell’insegnamento accademico, così lontana dai modi della pittura di Omar Hassan. Confrontandosi con quelle forme imperiture, l’artista compie un atto di umiltà e di verifica, quasi volesse testare la validità del suo segno nell’orizzonte temporale della storia dell’arte. Non si possono interpretare gli interventi di Hassan sui calchi classici come estemporanei, quanto tardivi, gesti d’irriverenza verso l’antico. Si tratta piuttosto di gesti di appropriazione e, insieme, di vivificazione del linguaggio classico. Non c’è dubbio che, presto o tardi, anche l’arte urbana assurgerà alla dimensione del classico. Ma, intanto, almeno per Hassan, questo dialogo ha il senso di un riordinamento delle pulsioni creative in una dimensione più adulta, che lo obbliga a misurare il proprio linguaggio con quello aureo della tradizione. In fondo, è un confronto cui molti artisti si sono sottoposti anche nella storia più recente, basti pensare alla Venere restaurata di Man Ray, alla Venere degli stracci di Pistoletto, al Picasso del Ritorno all’Ordine, a De Chirico, a Dalì e a numerosissimi altri maestri del Novecento. Questa “corrispondenza d’amorosi sensi” tra l’antico e il moderno suppliva a una mancanza di confronto con la natura stessa e con un’idea di bellezza che a noi contemporanei sembra quanto mai inattuale. Johann Johachim Wincklemann scriveva che “la differenza fra i greci e noi” - e alludeva ovviamente agli uomini del Settecento – “sta in questo: che i greci riuscirono a creare queste immagini, anche se non ispirate da corpi belli, per mezzo della continua occasione che avevano di osservare il bello della natura: la quale, invece, a noi non si mostra tutti i giorni e raramente si mostra come l’artista la vorrebbe”.

Immaginate, ora, quanto il concetto del bello in natura sia distante dalla mente di uno street artista, cresciuto in mezzo alla disarticolata topografia metropolitana di un quartiere come Lambrate, e quanto difficile possa essere l’assimilazione di un ideale estetico che non trova alcun riscontro nella sua quotidianità, e avrete la misura dei rischi che Omar Hassan ha accettato di correre. Abituato a tracciare segni sul muro, l’artista non solo ha riportato su tela quegli stessi gesti, quelle impronte gioiose formate da una moltitudine di colori, ma le ha trasferite perfino sulle icone più sacre dell’arte occidentale, portando, così, a compimento un’ulteriore sintesi: quella tra la dimensione prosaica dell’arte contemporanea e quella auratica dell’età dell’oro. E, en passant, è bene ricordare che la scultura classica era policroma e non monocroma, come tramandatoci dal Canova. Dunque, Hassan non fa che restituire alla classicità la dimensione del colore.

Accanto alle Vittorie alate, alle Veneri mutile, rianimate da una fragrante fioritura di colori sintetici, Hassan dispone, infatti, una serie dissonante di objects trouvés, di scarti da discarica, come il succitato WC o un frigorifero riempito di bombolette usate. L’accostamento è dei più stridenti, ma rivela l’intrinseca dicotomia estetica dell’artista. La pratica dadaista del recupero, già divenuta un classico nella contemporaneità, si spinge in Omar Hassan fino a esiti estremi. E così, i suoi stessi strumenti di lavoro, diventano un’opera d’arte.

Allineate e sigillate in teche di perpex, le bombolette esauste diventano, quindi, traccia concreta e testimonianza oggettiva di una pratica, assumendo al contempo una valenza artistica, un po’ come accade per le foto che documentano le azioni performative. Ne sono un esempio, le opere della serie Borgio Verezzi in wonderland, che assemblano le bombolette consumate durante l’esecuzione di un dipinto murale eseguito nell’omonima cittadina ligure. Da una sola azione, in questo caso, nascono due diverse espressioni artistiche, la prima pittorica e performativa, la seconda inerente la prassi del ready made. Ed ecco un’altra sintesi, che questa volta ricompone l’annosa dicotomia tra pratiche pittoriche e concettuali. E la riprova di questa attitudine è il fatto che non solo la bomboletta spray assume il valore di opera d’arte, come nella succitata serie, ma diventa perfino il soggetto di una scultura bronzea, portando così a compimento quel processo di fagocitazione del classico, iniziato con gli spruzzi sui calchi in gesso. Si tratta di un’opera che racchiude la sostanza di questo scambio tra classicità e modernità, poiché in essa, la bomboletta (dotata di cinque tappi con i colori primari, il bianco e il nero, quasi a indicare tutta l’estensione della gamma cromatica) e l’atto stesso di spruzzare vernice, ascendono alla dimensione monumentale e iperurania dell’antico. Si tratta, in definitiva, di una sorta di altare dei writer, un idolo consegnato alla futura memoria dei posteri.

Nell’arte di Omar Hassan tutto sembra rispondere a questa necessità di ricomposizione, a questa volontà di unificare influenze, matrici ed elementi discordanti della sua biografia. Non si insiste mai abbastanza, nell’analisi di una ricerca, sugli elementi biografici, forse per una sorta di riguardoso pudore, ma nel caso di Hassan è lecito almeno dire che il mezzo e il modo, fuor di metafora la bomboletta e lo spruzzo, hanno un significato preciso. Sono strumenti che servivano a computare sul muro del suo studio la frequenza di un gesto quotidiano, l’assunzione di un farmaco. Nasce così lo spruzzo singolo di Omar Hassan, come una enumerazione di vitale importanza, in attesa che presto l’atto si trasformi in automatismo. Così, dentro quello spruzzo di spray c’è il senso stesso della vita, c’è il suono del respiro e il colore dei giorni. E, infine, c’è la volontà di permeare ogni gesto e ogni cosa con questo soffio di energia. La stessa che il filosofo Henri Bergson definiva élan vital.